The Politician Factory: How Western Democracies Select Performers, Not Builders - Deep Dive

TL,DR

get the short version

Political Elites in Western Democracies: Motives, Traits, and the STEM Gap Since WWII

Post-WWII Democratic Practice: Elite Governance in Western Democracies

In the decades following World War II, Western democracies largely operated on a model of “democratic elitism.” This theory, famously articulated by Joseph Schumpeter and others, holds that mass democracies are governed by competing elites rather than by direct rule of the people[1]. In practice, this meant a professional political class emerged to mediate between citizens and the state. Elected representatives – often from similar social and educational backgrounds – became the decision-makers, with voters choosing periodically among rival teams of these elites in free elections[1]. Governing in Western Europe and North America thus settled into a pattern of party-based elite governance, tempered by liberal institutions like independent judiciaries and a free press. Political scientist John Higley observed that this post-war consensus accepted that “elitist mediation is inevitable in mass democracies”, so long as elections are free and institutions autonomous[1].

Under this model, career politicians became commonplace. Over the post-war era, politics increasingly professionalized: many officeholders treated politics as their full-time career, often after early involvement in party youth wings or staff roles. Max Weber had noted that professional politicians are “crucial for effective democracy”, providing expertise in governance[2]. Indeed, Western political systems came to be dominated by individuals who spent most of their working lives in public office or political work. This brought stability and policy experience, but also a certain homogeneity in political leadership. Whether in Washington, London, Bonn/Berlin or Paris, the halls of power filled with a fairly narrow slice of society – typically well-educated, middle- or upper-class men (and gradually more women over time) with backgrounds in law, public administration, or business. The Iron Law of Oligarchy, as Robert Michels put it, seemed to operate even in democracies: organization leads to oligarchy, concentrating power within a political class.

Traditional policymaking in these democracies has been characterized by incremental change and complex compromises brokered among these elites[3]. Grand ideological clashes gave way to technocratic management and consensus-building (especially under the post-war welfare state consensus in Western Europe). However, one consequence of this elite-driven system has been growing public disillusionment. In recent years, populist movements across the West have railed against “establishment politicians,” tapping into frustration that career politicians are disconnected from ordinary people. The rise of populism in the 2010s and 2020s has been fueled by an erosion of trust in traditional institutions and in “experts”[3][4]. When mainstream leaders are perceived as self-interested or out of touch with working citizens, public trust in the political class collapses – and, alarmingly, this distrust can extend to scientific and policy experts tied to the establishment[4]. As Angela Merkel warned in 2021, democracy “lives on [...] trust in the facts,” yet that trust is fragile[5].

Who Enters Politics in Western Democracies?

What kinds of people are drawn into public political life, and why do they pursue these demanding careers? Western democracies pride themselves on open opportunity to run for office, but in reality the pool of political entrants is self-selecting. Several patterns have emerged since WWII regarding the motivations, personalities, and backgrounds of those who become politicians.

Motivations: Public Service vs. Personal Ambition

On the surface, most politicians profess noble motives – a desire to serve the public, advance an ideology, or “make a difference” in society. Indeed, many do begin their careers with genuine idealism. Interviews with political figures find that most enter politics sincerely believing in a cause or community service ethos[6]. For example, British political scholar Bill Jones notes that MPs genuinely think they can “fulfil an idealistic sense of service to the community” when they first stand for office[6]. This idealism – whether it’s commitment to civil rights, economic reform, or national service – is often a real part of the initial drive.

At the same time, private and personal motives undeniably play a powerful role. Politics is inherently about power and status, and those who pursue office tend to be ambitious individuals. Jones emphasizes that “political activity is essentially about the winning and retaining of power to change the way other people live their lives,” and acknowledges the “dangerous” reality that for some it becomes “power for its own sake.”[7]The allure of high status – prestige, influence, public recognition – can be a strong incentive. Political office brings visibility and often respect (or notoriety), which appeals to those with a strong drive for status or validation. For example, psychological studies have found that people with narcissistic tendencies are disproportionately likely to engage in politics. One large study in the U.S. and Denmark revealed a positive correlation between narcissism and political participation – the more narcissistic an individual is, the more likely they are to attend meetings, contact officials, donate, and even vote in midterms[8]. In the researchers’ words, “individuals who believe they are better than others engage in the political process more.”[9] This suggests that those with large egos or a thirst for recognition self-select into political activism and candidacies at higher rates than more modest citizens.

Beyond ego and power, other personal motives include security and career ambition. In many Western countries, holding public office comes with a stable salary, benefits, and influence that can be parlayed into post-political careers (consulting, lobbying, media, etc.). For some, a political career offers a clear ladder of advancement (councilman to mayor to congressman, etc.) and a secure niche in the societal elite. “Political junkies” or those “addicted to the politics bug” often thrive on the competition for advancement, relishing the game itself[10]. Politics can indeed be “addictive” – politicians often describe the rush of campaigning and the drive to win as something that gets in the blood[10]. As one UK minister put it, once people catch the politics bug, they feel compelled to “compete against fellow addicts for the limited places at the very top.”[10]In short, those who choose politics as a career tend to be high-achieving, power-seeking individuals, often balancing a genuine belief in public service with a hefty dose of personal ambition, competitiveness, and desire for significance.

Dominant Personality Traits of Political Leaders

Given these motivations, it’s no surprise that certain personality traits are overrepresented among successful politicians. Studies by political psychologists, as well as anecdotal observations by colleagues, converge on a portrait of the “typical politician personality.” It is a complex mix: part idealist, part pragmatist, part egotist. Bill Jones, after analyzing numerous ministerial careers, concluded that “success in politics seems to be an admixture of driving ambition, narcissism, [and] genuine idealism with, perhaps, a dash of daring and necessary ruthlessness.”[11] In other words, top politicians usually possess intense ambition, often above-average narcissism, resilience (thick skin), openness to risk, and yet also some degree of idealistic conviction or vision. This cocktail of traits helps them endure the spotlight and cutthroat competition while maintaining a sense of purpose.

Certain “dark” traits have drawn research attention. A body of work on the Dark Triad in politics examines narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy among leaders[12][13]. While full-blown psychopaths are (fortunately) rare in elected office, mild expressions of these traits can be advantageous. For example, narcissism – a grandiose self-image and craving for admiration – may help politicians project confidence and persist despite criticism. As noted, narcissistic personalities are more likely to seek leadership roles and participate politically[8]. Machiavellianism – being cunning, strategic, and amoral in pursuing goals – can aid politicians in outmaneuvering rivals and negotiating deals. And a dose of psychopathic traits (such as fearlessness or lack of emotional inhibition) might bolster the “raw courage” and stamina needed for high office[14][15]. Indeed, Jones found that “humor, charm, and raw courage” ranked among crucial characteristics for leaders[14]. The most effective politicians often exhibit exceptional charm/charisma, the ability to connect with and persuade others. They tend to be extroverted and socially assertive – campaigning and public speaking demand high energy and comfort with crowds. Optimism and resilienceare also common: successful leaders are often those who can endure setbacks (electoral defeats, public criticism) and bounce back with undiminished zeal[15].

On the cognitive side, politicians generally boast strong verbal skills and memory. In parliamentary systems like Britain’s, a “mastery of the spoken word” is practically a prerequisite for advancement[16]. Debating, quick rebuttals in interviews, and rally speeches call for verbal agility and confidence. Many politicians also have remarkable memory for names, faces, and policy details – useful for both retail politics and complex legislative work[15]. Additionally, a degree of conscientiousness (discipline and work ethic) is necessary to handle the demanding schedules and information loads, though perhaps not as high as in some professions since political success also rewards improvisation and adaptability. Interestingly, while integrity and honesty are traits voters say they desire in leaders, the reality is that cunning and flexibility (even a willingness to bend the truth) can confer advantage in the political arena. This creates a tension in the character profile: politicians must appear honest and principled to win trust, yet many are adept at calculating, strategic behavior when cameras are off.

In summary, the dominant personalities in Western political careers tend to be charismatic alpha types – high in ambition and confidence, able to handle conflict and public scrutiny, often fueled by ego and desire for power, but typically also driven by some genuine belief or vision. They are, as Jones quips, “strange, special people” with a near-“narcissistic interest in themselves” who nonetheless might sincerely believe in serving the public[6]. This dual nature – part self-serving, part service-oriented – is a hallmark of many political personalities. Psychological analysis supports this: politicians often rate higher on traits like narcissism and ambition than the general public, but also exhibit greater civic engagement and leadership orientation, suggesting a blend of self-focus and group-focus.

Career Paths and Educational Backgrounds of Politicians

Another way to understand who enters politics is to look at their backgrounds. Across Western democracies, political elites have historically come from a narrow range of professions and education. A striking pattern is the dominance of lawyers, economists, and party apparatchiks, and the relative scarcity of scientists or technical professionals in elected office. Politics has a strong tradition of being a lawyer’s domain – indeed, legal training is often seen as ideal preparation for writing laws and debating in legislatures. In the United States, for example, Congress has long been filled with former attorneys and businesspeople. As of the mid-2010s, roughly 40% of U.S. Senators and a significant share of House members held law degrees, while hardly any came from pure science or engineering careers[17][18]. Peter Thiel pointed out in 2014 that fewer than 35 of 535 members of the U.S. Congress (under 7%) had backgrounds in science or technology, lamenting that the “rest don’t understand [modern technology]”[17]. By contrast, well over half of Congress members had backgrounds in the law, business, or public service/politics fields. A similar situation exists in the UK: a recent analysis of British politicians found that law and politics graduates are heavily overrepresented. In the 2017 general election, 15% of parliamentary candidates held a degree in law and 16% in political science, compared to only 9% with STEM degrees[19]. History and economics degrees were also common among candidates, whereas fields like engineering or computer science were rare[19]. This reflects the feeder paths into politics: studying law or politics, then working in government, think-tanks, or party offices, is a typical trajectory into public office.

Why do these backgrounds dominate? One reason is self-selection and interest. As data scientist Andrew Gelman observes, “the kind of people who want to go into politics in the first place are likely to study political science and get law degrees.”[18] Young people with political ambitions often gravitate to subjects that directly relate to governance, or they quickly move into political jobs after university. On the flip side, those who pursue careers in science, engineering, medicine, etc., may have less inclination or opportunity to pivot into politics later (a phenomenon we explore in the next section). Political parties also play a gatekeeping role: they recruit from networks of party activists, lawyers, and former aides – a pool of “usual suspects”that tends not to include, say, research scientists or tech entrepreneurs. Over time, this has created a somewhat insular political class. For example, Britain’s Parliament has been disproportionately filled with alumni of elite schools (like Eton) and Oxford/Cambridge, often studying PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics) or law – a training ground for future cabinet ministers[20]. Germany’s post-war Bundestag similarly saw many lawyers, civil servants, and career politicians rising through party ranks, with fewer coming from technical fields or manual trades. In France, the dominance of graduates from École nationale d’administration (ENA) and other grand écoles in politics meant that many leaders were technocrats in economics or public administration by training, but again not typically scientists or engineers. (One notable exception: President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing had an engineering background from École Polytechnique alongside his ENA credential, and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany holds a PhD in physical chemistry – both rare cases of top leaders with hard science training.)

In essence, Western political elites have been an educated elite, but not a scientifically representative one. They usually have strong backgrounds in law, policy, economics, or military service – fields directly relevant to wielding power. This can yield valuable skills (legal reasoning, economic literacy, administrative experience). However, it also means that legislatures and cabinets may lack diversity in expertise, especially in scientific and technical domains. The next section delves deeper into this underrepresentation of STEM professionals in politics, its causes, and why it matters.

The Underrepresentation of STEM Professionals in Politics

One prominent facet of modern Western democracies is the chronic underrepresentation of individuals with STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) backgrounds in elected office. Despite the centrality of science and technology to contemporary societal challenges – from climate change to digital privacy to public health – relatively few scientists or engineers sit at the tables of power. This trend is observable across multiple countries.

The Extent of the STEM Gap: Data and Examples

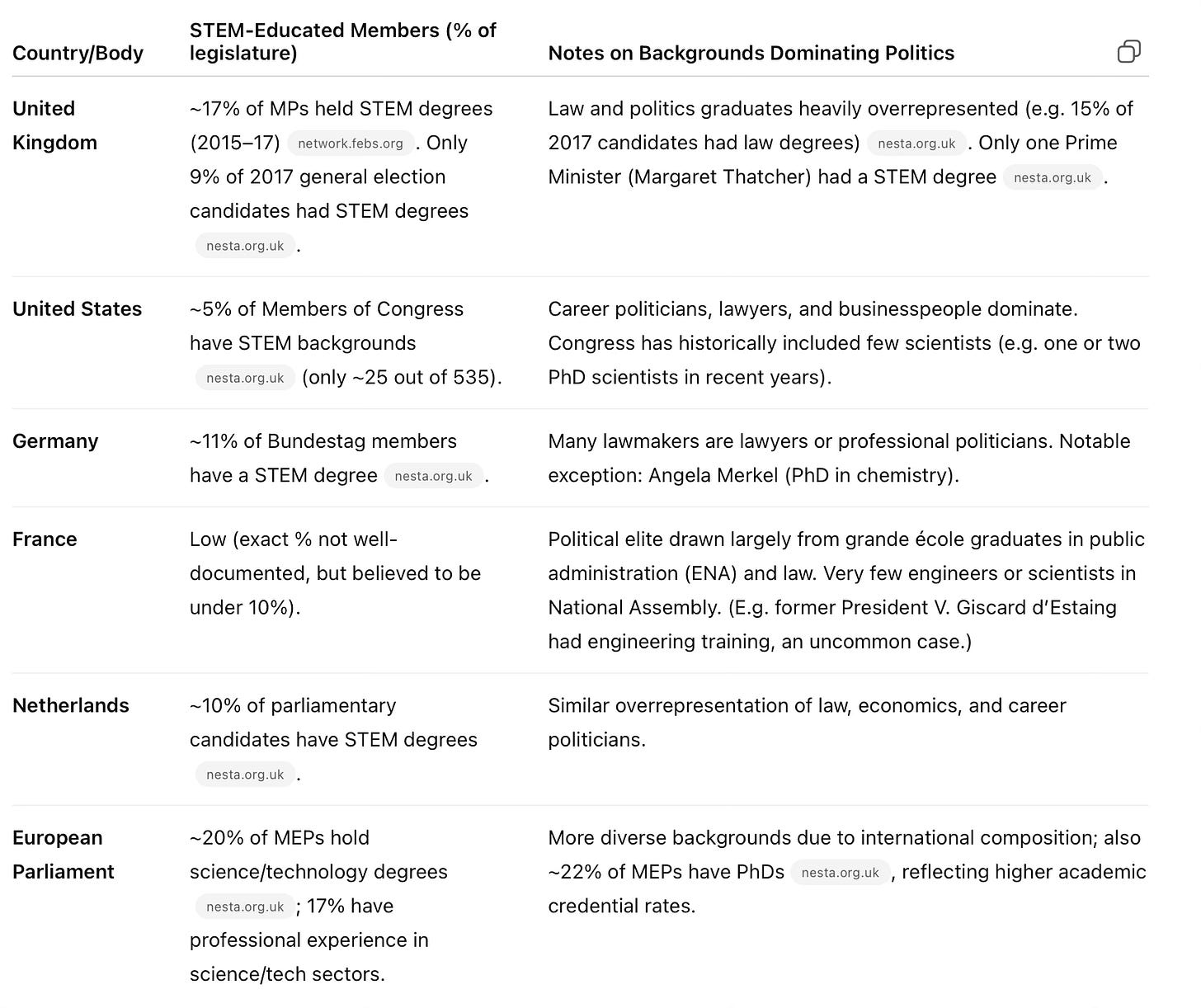

Data on legislators’ education illustrates the gap between STEM fields and other backgrounds. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the 2015–2017 Parliament had 541 MPs with higher-education degrees, but only 93 of them (17%) held degrees in STEM subjects[21]. This is strikingly low considering that in recent years about 46% of UK university graduates earned STEM degrees[21] – meaning Parliament was far less scientifically educated than the general graduate population. Moreover, only two MPs in that Parliament held a PhD in a STEM field[21]. In contrast, degrees in the humanities, social sciences, and especially politics and law were far more common among MPs. The trend holds among those seeking office as well: an analysis ahead of the UK’s 2017 election found only 9% of major-party candidates had a STEM degree, versus 41% of recent UK graduates overall[22]. By comparison, 15% of candidates had law degrees and 16% had studied politics, indicating a skew toward those disciplines[19].

Other Western democracies show similar patterns. In Germany, which actually has a strong engineering tradition in its economy, the proportion of scientists in politics is still modest. Roughly 11% of members of the German Bundestag have a background in the natural sciences or engineering – only marginally higher than Britain’s share[23]. Germany’s most famous scientist-turned-politician, Angela Merkel, is the exception that proves the rule: her doctorate in chemistry stands out in a political class largely composed of lawyers, business administrators, and career party functionaries. The story repeats in the Netherlands, where about 10% of parliamentary election candidates held STEM degrees in a recent election[24]. And in the United States, the gap is even wider: only about 5% of U.S. Congress members have a STEM degree or professional background[25]. In 2023, that amounted to perhaps two dozen out of 535 legislators with any scientific or technical training – a tiny fraction. The U.S. has had only a handful of PhD scientists or engineers in Congress over the past decades (examples include former Rep. Bill Foster, a physicist, and Rep. Rush Holt, also a physicist). The vast majority of American lawmakers come from law, business, or political careers.

There have been a few notable exceptions where STEM professionals reached top leadership, but these are rare. The UK has only ever had one Prime Minister with a science degree – Margaret Thatcher, who studied chemistry (and briefly worked as a chemist)[26]. Harold Wilson had studied economics but worked as a statistician during WWII, a partial brush with a technical field[26]. In Germany, Merkel’s scientific background is often credited with bringing a pragmatic, data-informed style to her decision-making. France’s post-war leaders, by contrast, have predominantly come from elite civil service schools (ENA) or political careers, with virtually no one from a laboratory or engineering firm rising to high office lately. The European Parliament interestingly has a higher share of STEM degree holders (around 20% of MEPs hold science or technology degrees)[27] – perhaps due to its composition from many countries, including Eastern European states where engineering in the older generation of politicians is more common. That said, even 20% is far from proportional to the population. The Table below summarizes some data on STEM representation in politics:

Despite minor differences, the consistent theme is that STEM professionals are a small minority in most Western political institutions. This disparity is often larger than other demographic gaps (for example, gender gaps are narrowing gradually, but the expertise gap remains wide).

Why Do So Few Scientists and Engineers Enter Politics?

Multiple factors – both “supply-side” (who is willing/able to run) and “demand-side” (who parties and voters choose) – contribute to the underrepresentation of STEM individuals in politics:

Self-Selection and Career Interests: Many scientists and engineers simply do not want to go into politics. The personality profile and interests that lead someone into a STEM career often differ from those that lead to political ambition. As one commentator wryly noted, “the vast majority [of engineers] would have zero interest in running for office. If they’d had that interest, maybe they’d have gone to law school.”[18] The commitment to a scientific vocation – spending years in labs or technical roles – may leave little appetite for the very different world of campaigning, speeches, and parliamentary infighting. In short, there is a supply problem: comparatively few people with STEM backgrounds ever consider standing for election. This may reflect temperament (those drawn to analytical work might find politics too combative or superficial) and values (preference for meritocracy and empiricism over the compromises of politics).

Cultural and Institutional Pipeline: The professions of law and politics have an established pipeline into public office, whereas STEM fields do not. For decades, law firms have informally encouraged lawyers to enter public service or run for office, recognizing that “law influences policy and policy influences law.” Many politicians begin their careers as lawyers, and their firms or networks support their political aspirations. By contrast, “scientists and scientific careers don’t have that type of culture.”[28] Academia and industry seldom prepare or encourage scientists to jump into electoral politics. There are few mentorship programs or incentives for, say, a successful engineer to run for city council or parliament. In fact, pursuing politics might be seen as leaving one’s field or “going to the dark side.” This cultural difference means STEM professionals often lack the support structures, role models, and skillsets for political entry. As Shaughnessy Naughton (founder of the pro-science 314 Action group) noted, when she first ran for Congress as a chemist, “I knew how to be a chemist, but I didn’t know much about being a candidate” – there was no built-in guidance for scientists to transition into campaigning[29][30].

Party Recruitment and Gatekeeping (Demand-Side): Political parties historically have not prioritized recruiting STEM candidates. Party gatekeepers often favor those with political experience, community name recognition, or legal expertise. A scientist with no prior political profile might struggle to be selected as a candidate by major parties. This is changing slightly – e.g. France’s Emmanuel Macron tapped a few experts for his government, and some parties occasionally run doctors or scientists in elections – but generally, party elites come from the same milieu they always have. The “political class” tends to reproduce itself. Even wealthy donors who claim to want more technocrats in office often end up backing familiar profiles. An analysis of candidates supported by tech billionaire Peter Thiel found that despite complaining about lack of science knowledge in Congress, Thiel’s funded candidates in 2022 were almost all law or business graduates, not scientists[17][31]. Gelman dryly observes this “shows how the law community’s domination of our government continues: even funders who think we need more scientists still end up throwing money at lawyers.”[32] In short, the political system’s demand for candidates gravitates toward certain credentials (law degrees, political staff experience, etc.) and not STEM backgrounds.

Skills Mismatch and Perceptions: Stereotypes hold that scientists are “too logical and not charismatic enough” for politics[33]. While certainly many scientists are perfectly charismatic, there is a perception that the skills needed to win elections – persuasive oratory, retail politicking, emotional appeal – are not prevalent in the scientific community. Conversely, a brilliant researcher may be frustrated by the oversimplification and sloganeering of political discourse. Some engineers might find the lack of clear “right answers” in policy-making uncomfortable compared to technical problem-solving. These differences in professional culture can be a barrier. Additionally, politics often involves endless meetings, negotiations, and deal-making; those who prefer the straightforward logic of science might be turned off by the ambiguity and compromise inherent in governance. (Of course, many lawyers and businesspeople also dislike these aspects, but they are more acclimated to them from their training.) The net effect is that fewer STEM professionals develop the nascent political ambition – as political scientists term it – to consider a run for office, and even fewer follow through to become candidates.

Political Alignments: In the U.S. context, there’s an interesting partisan element: a large majority of scientists identify as liberal or moderate, not aligning with conservative parties[34]. This has meant center-left parties (e.g. Democrats in the U.S.) are more likely to field scientists, whereas conservative parties have a thinner bench of STEM talent interested in running. Even globally, STEM fields have been associated with liberal, technocratic political attitudes, which might not align with populist currents. This dynamic can further limit the pool of scientists in politics on certain sides of the spectrum. (However, historically some countries like the former Soviet Union or China had many engineers in leadership – showing this is a cultural/political choice, not an inevitability of science itself.)

Recognizing these barriers, some initiatives have sprung up to encourage more STEM candidates. In the U.S., for example, non-profits like 314 Action explicitly recruit and train scientists to run for office, aiming to “elect more scientists to Congress, state legislatures, and local offices.”[35][36] They argue that in an era of climate change and pandemic risk, having scientifically literate lawmakers is crucial. Similarly, advocacy from scientific communities calls on researchers to engage more with policy and even stand for election, to bridge the expert-politician divide[37][38]. These efforts have seen some success – e.g. the 2018 U.S. midterms saw a small wave of STEM professionals (such as a nurse, a pharmacist, a few engineers) winning congressional seats. Nonetheless, the overall landscape remains that Western democracies are largely led by non-scientists, and that is unlikely to change dramatically overnight.