The 50-Cent Dollar/Euro: How Public Spending Loses Half Its Value Before It Hits the Ground

Expanding Fiscal Footprint: EU and US Government Spending Since the Marshall Plan

Introduction

In the aftermath of World War II, Western governments dramatically expanded their fiscal reach to rebuild economies and shape society. A defining starting point was the Marshall Plan (1948–1952), through which the United States Congress appropriated $13.3 billion (equivalent to roughly $150 billion today) to finance Europe’s reconstruction . This massive aid not only restored infrastructure and economies, but also set a precedent for using public spending as a tool of geopolitical influence and domestic development . In the ensuing decades, both Europe and the United States saw government expenditures surge to unprecedented levels, funding social programs, infrastructure, defense, and economic interventions on a grand scale.

By the late 20th century, government spending had grown from single-digit percentages of GDP in the early 1900s to very large shares in advanced economies . In Europe especially, public expenditure rose from around 10% of GDP at the end of the 19th century to nearly 50% of GDP in many countries by the 21st century . This reflected the construction of comprehensive welfare states – including universal healthcare, education, pensions, and social safety nets – as well as heavy public investments in industry and agriculture. In the United States, federal, state, and local government spending also climbed significantly (albeit to a lower plateau than in Europe), particularly with the advent of programs like the New Deal and later the Great Society initiatives of the 1960s. Major U.S. programs such as Medicare and Medicaid (launched 1965) expanded social spending, while Cold War defense outlays (and projects like the interstate highway system and NASA’s Apollo program) marked huge public investments in technology and infrastructure.

This expansion of the fiscal footprint had profound effects on society. Public spending became a central instrument for shaping economic outcomes and social welfare, contributing to reduced inequality through redistribution . In Western Europe, the broad-based social programs financed by high public outlays led to improved social indicators (from health and education to poverty reduction) and a more extensive social safety net than in earlier eras. In the U.S., government programs substantially lowered elderly poverty (through Social Security and Medicare) and invested in human capital (e.g. through the G.I. Bill for education). By the end of the 20th century, it was clear that government budgets had become powerful levers for influencing society – stimulating growth, smoothing business cycles, supporting vulnerable populations, and steering national priorities.

However, this vast expansion has also raised questions about efficiency and effectiveness. Critics note that while government spending can achieve broad social goals, it often suffers from “leakage” – i.e. resources not translating into intended outcomes due to various inefficiencies. In recent years, attention has turned to comparing this public-sector performance with the typically leaner, incentive-driven resource allocation of private capital. The following sections provide a detailed look at the inefficiencies (“leakages”) inherent in public spending and a comparison to private investment efficiency, before concluding with when government spending is nonetheless warranted despite these higher leakages.

Comparing Public and Private Efficiency

Public programs often appear efficient on paper, with audits reporting only modest error or waste rates – but in reality the true leakage in public spending is far higher once all inefficiencies are accounted for. For example, official audits in advanced economies indicate relatively low “improper payment” or error rates (around 5% of outlays in recent U.S. federal programs , and under 2% in EU budget expenditures after corrections ). Yet these audit figures capture only a fraction of the waste. A more complete accounting of leakage includes:

Administrative Overhead (≈2–3%) – A portion of public funds is absorbed by the bureaucracy itself. Even efficiently run programs incur costs for staff, offices, and administration. For instance, roughly 6% of the EU’s budget is consumed by administrative costs (under 3% just for civil service salaries) . Large U.S. social programs like Medicare manage to keep overhead as low as ~2% , but across government as a whole, administrative overhead on programs typically runs in the low single digits. This overhead directly reduces the share of funds reaching end beneficiaries or projects.

Cost Overruns and Ineffective Projects (≈10–25% or more) – Public works and initiatives frequently exceed their budgets or fail to deliver promised benefits, resulting in substantial waste. Numerous studies have found that major government infrastructure projects are almost chronically over-budget. In global surveys, 90% of large public projects blew past cost estimates, with average cost overruns around 28% and much higher in certain sectors (e.g. rail projects averaging +45% above projected costs) . Even routine government projects often face political pressure to underestimate costs and overestimate benefits at inception, leading to bloated final expenditures. Historical data in the U.S. and EU show many public investments coming in 10–25% or more above budget, implying that a significant share of public money buys less output than planned. Moreover, some government-funded projects turn out to be outright ineffective or under-utilized, essentially sinking taxpayer money into ventures with negligible social return (failed IT systems, underused infrastructure, etc.).

Deadweight Loss from Taxation (≈20–50%) – Unlike private investment, public spending is financed by taxes (or debt that ultimately relies on taxes), which impose economic efficiency costs. Taxes distort behavior and resource allocation in ways that shrink overall output, meaning each $1 of government spending often costs society more than $1 in lost economic activity. Estimates of this excess burden vary, but commonly 20–50% of the amount raised is lost as deadweight in the economy . In other words, the marginal cost of public funds is about $1.2–1.5 per $1 spent, due to reduced incentives to work, save, and invest . This hidden leakage – essentially the economic drag of taxation – does not appear on a budget sheet but is very real in terms of foregone output.

Inflationary and Macroeconomic Side-Effects – Large-scale government spending, especially deficit-financed, can produce macro “leakages” that erode the real value or impact of those expenditures. For example, when fiscal stimulus pushes demand beyond supply, it can fuel inflation, diluting purchasing power. A Federal Reserve analysis suggests that the hefty COVID-era fiscal packages contributed roughly 2.5 percentage points to U.S. inflation in 2021–22 by overheating demand . Likewise, persistent deficit spending leads to rising public debt, which tends to raise interest rates and crowd out private investment . The Congressional Budget Office estimates that for every additional dollar of U.S. federal deficit, private investment falls by about 33 cents as a result of higher interest rates and resource diversion . These side-effects mean some benefits of public spending are offset by economy-wide costs – whether in higher prices or reduced private-sector growth.

Absorption Delays and Under-Utilisation of Funds – Government appropriations often face bureaucratic hurdles, slow roll-outs, or capacity constraints that delay or dilute their impact. In the EU, it is not uncommon for countries to leave significant portions of allocated funds unspent within the budget period. For instance, as of 2020, major beneficiaries of EU structural funds like Spain and Italy had absorbed only ~40% of the funds available from the 2014–2020 cycle, with the rest delayed or unused . Such lags mean intended projects or programs either happen years late or never fully materialize, lessening the societal impact. Similarly, in many public agencies, end-of-year spending spurts (“use it or lose it” behavior) can result in rushed, suboptimal use of funds, while other budgeted sums simply remain idle. These inefficiencies of timing and utilisation further widen the gap between money spent and value delivered.

In sum, when one accounts for all these factors – from administrative costs and project overruns to the indirect economic costs and delays – the effective leakage in public spending can far exceed the modest 5–7% error ratesfound in audits. By some estimates, 30–50% or more of public funds’ potential impact is lost to such leakages in many domains. This raises the question: could the private sector allocate resources more efficiently?

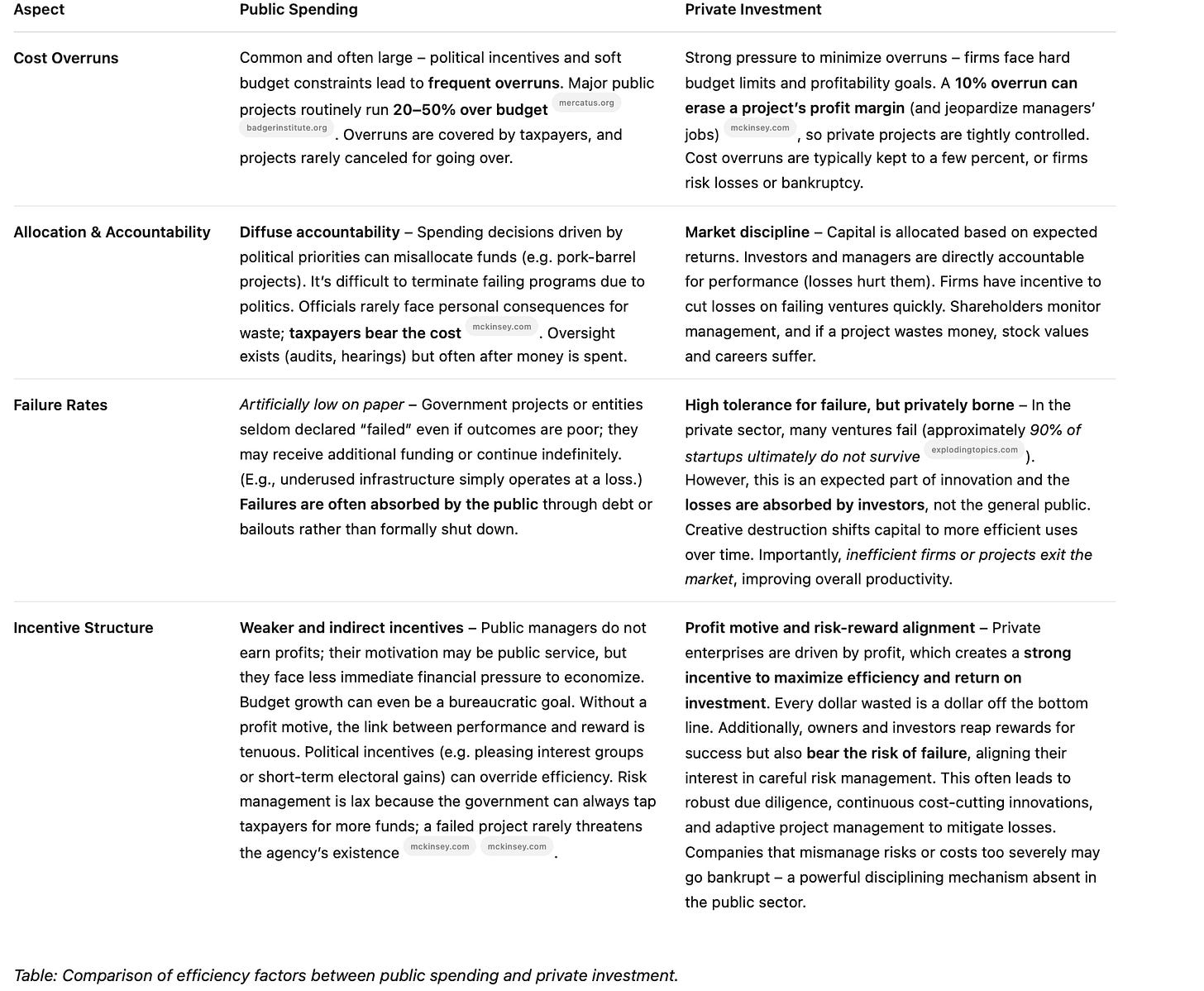

Private investment indeed operates under very different incentives and constraints, which generally lead to leaner, more efficient resource use. The table below contrasts key efficiency aspects of public vs. private investment:

Table: Comparison of efficiency factors between public spending and private investment.

As the table highlights, private capital deployment tends to be more disciplined and efficiency-driven. In practice, private firms typically cannot afford anything near the kinds of overruns or delays that often plague government-funded works, because doing so directly threatens their survival or profitability. Accountability mechanisms in the market (from shareholder oversight to competition) enforce a level of rigor that bureaucratic agencies struggle to match. Moreover, the ability to pull the plug on bad projects – while painful for investors – ensures capital is reallocated to more productive uses, something governments find politically very difficult (resulting in money sunk into “white elephant” projects or endless program bailouts).

It is worth noting that private investment is not without inefficiency – companies can make poor investments and suffer losses, and markets are prone to booms and busts. But the key difference is in who bears the cost of inefficiency. In the private sector, it is the investors and firms themselves (and ultimately, in competitive markets, those entities get punished or weeded out), whereas in the public sector, the costs of missteps are borne by taxpayers and the broader economy. This dynamic generally makes private actors more prudent with money than public agencies.

Of course, not all domains of the economy are equally suited to private vs. public provisioning. The superior efficiency of private capital holds true in most normal commercial domains or where goods/services are excludable and for-profit provision is viable. In sectors like consumer goods, technology development, many services, and even infrastructure construction, market competition and private entrepreneurship tend to allocate resources in ways that maximize output relative to input, provided that property rights and markets function well.

Conclusion

The historical record of the past 5–6 decades demonstrates that both the EU and US governments have used ambitious fiscal spending to shape society – from rebuilding war-torn Europe and expanding social welfare, to driving technological innovation and regional development. This activist public spending undeniably delivered many benefits: it helped establish social safety nets, improved access to education and healthcare, built highways and railways, and guided economies through recessions. In Europe, high public outlays underwrote a level of social protection and equality far beyond what existed in the early 20th century. In the United States, federal spending initiatives supported the elderly and poor, put men on the moon, and spurred innovation (the internet and GPS trace back to defense-funded R&D). These public investments have profoundly influenced societal outcomes, often for the better.

However, the analysis of inefficiencies and leakage reveals a critical insight: government spending, by its very nature, entails substantial overhead and waste that private sector spending might avoid. A significant share of every public dollar is diverted to administrative costs, lost to cost overruns or suboptimal projects, or diluted by the economic frictions of taxation and inflation. By contrast, private capital is generally more nimble and strictly accountable to results, leading to more efficient resource use in competitive environments. Empirical evidence shows that, outside of pure public goods, private enterprises usually deliver a given service or product at lower cost and with greater innovation than a monopolistic government provider, precisely because market incentives reward efficiency and punish failure.

Does this mean that all government spending is bad or unjustified? Not at all. There are crucial areas where government spending is not only justified but essential despite higher leakage. Public goods – things like national defense, basic scientific research, or infrastructure with large network effects – would be under-provided by private markets due to free-rider problems . Government intervention is warranted to ensure these goods are available, even if it means tolerating some inefficiency. Similarly, expenditures that address externalities (e.g. subsidies for public health or education, which have spillover benefits ) can increase overall welfare even if government is less efficient, because the market on its own would not account for those broader benefits. Social equity and safety-net programs are another domain where society may consciously accept a bigger government role – and the leakage that comes with it – in order to achieve outcomes like poverty reduction or universal access to healthcare, which markets alone might not deliver in an equitable way. In macroeconomic crises or recessions, countercyclical public spending (stimulus) may be necessary to stabilize the economy, even recognizing that such spending will not be perfectly efficient. In short, government spending is often justified as a tool to correct market failures or achieve social goals that we collectively value, despite its higher inherent costs.

The key, therefore, is to strike the right balance. Governments in the EU, US, and elsewhere should remain mindful of the high leakage rates detailed above and limit large-scale spending to areas where it is truly justified – where the unique benefits of public provision (or the urgency of need) clearly outweigh the efficiency losses. Robust institutional checks – audits, outcome evaluations, and transparency – can help mitigate some inefficiencies by holding public agencies closer to performance standards. Innovations like public-private partnerships (which leverage private-sector expertise in execution) are increasingly used to marry public goals with private efficiency . Ultimately, the past decades have taught us that while government spending can profoundly shape society, it works best when targeted to domains of genuine public interest and when public institutions strive to mimic the incentive structures that drive efficiency in the private sector. In most areas of the economy, private capital allocation remains the more efficient mechanism, so the government should focus its resources on the missions only it can fulfill – accepting some leakage as the price of pursuing those broader social objectives, and continuously seeking to minimize that leakage through better governance and accountability.

Sources:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to reflections from a nerd to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.