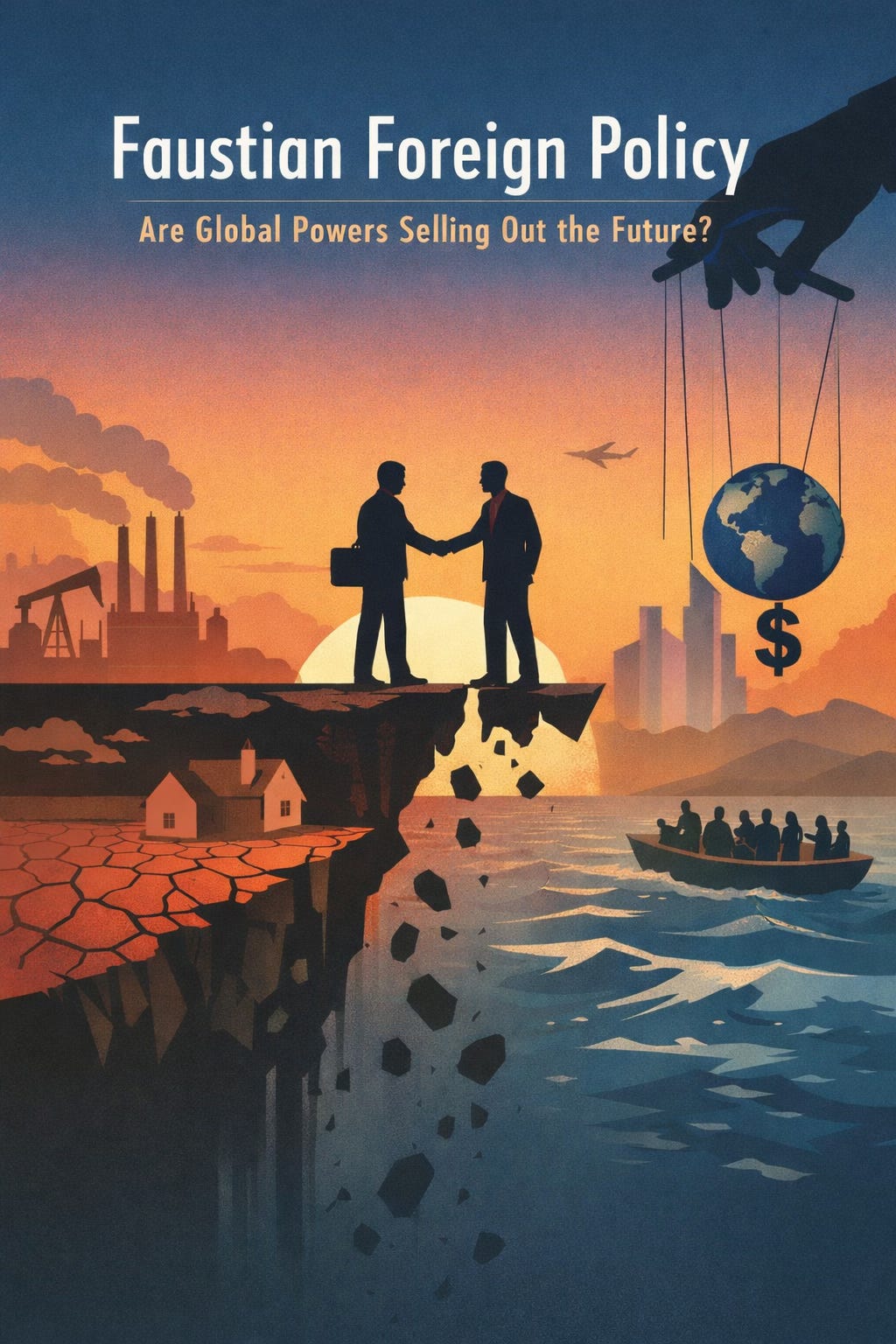

Faustian Foreign Policy: Are Global Powers Selling Out the Future?

Geopolitics: From Short-Termism to Transactionalism

Short-Term Thinking in Geopolitics

Geopolitics has often been characterized by short-term, short-sighted decision-making. Elected leaders frequently focus on immediate gains or the next election cycle, rather than long-range strategy. This “political short-termism” has been exacerbated by modern media pressures – as one analysis notes, social media’s demand for instant responses means governments face “expectations on governments for immediate solutions to complex problems,” making sustained attention to long-term issues difficult . The result is a tendency toward reactive policies that seek quick wins but “nurtures ‘short-termism’ in thought and action” . In many democracies, this has led to an “all politics, all the time” mindset at the expense of “considered policy analysis”, with too many ad-hoc priorities and not enough strategic follow-through .

Such short-sighted governance has left many structural challenges unaddressed. Complex issues like climate change, migration, and rapid technological disruption require forward-looking solutions, yet past leaders often kicked the can down the road. Voters and policymakers grew frustrated as traditional bureaucratic planning struggled to navigate a “far more complex technological world” of globalization and digital transformation. This frustration helped fuel populist backlashes in the 2010s, as many citizens felt that establishment politicians’ incremental visions were failing to “steer us” effectively into the future. The stage was set for a dramatic shift in how geopolitics is conducted.

The Rise of Transactional Geopolitics

Into this environment stepped leaders who promised to shake up the old way of doing things. Donald Trump’s approach is a prime example of geopolitics gone “full transactional.” Trump, with a background in aggressive real estate deal-making, brought a zero-sum mindset to foreign policy . For him, every interaction was a deal to be won or lost, with “one party’s gain” inevitably meaning “another’s loss” . He openly prioritized short-term U.S. advantages “at the expense of values, alliances, and even treaties” – viewing global agreements not as binding commitments, but as negotiable transactions. This manifested in nakedly opportunistic moves: for instance, Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris Climate Accord, and pressed allies on trade and defense spending in brusque “what’s in it for us” terms . Such actions reflected a “transactional myopia” – a narrow focus on immediate wins for the U.S., even if it meant undermining long-term partnerships or global stability .

Trump’s “America First” stance was in many ways a reaction to the short-sighted politics before him. He capitalized on the perception that prior leaders’ half-measures and lofty rhetoric had failed to deliver tangible benefits. By treating geopolitics like a series of business deals, Trump tapped into public desire for decisive action. However, this full transactionalism represents an extreme swing of the pendulum. While all leaders engage in transactions to a degree, what distinguished Trump was his “unabashed opportunism” and willingness to jettison long-held norms for short-term gain . This approach has raised profound questions: Is hyper-transactional geopolitics a corrective to past short-termism – or simply a different, potentially worse form of short-sightedness?

The Transactional Trap: Short-Term Wins, Long-Term Risks

There is growing evidence that a purely transactional worldview can go badly wrong in the long run. Critics argue that when nations abandon steady strategy for ad-hoc deals, the result is a more unstable and competitive world. A commentary on global trends warns that “the world risks shifting toward a hyper-transactional paradigm where narrow, short-term interests override collective benefits” . In such a paradigm, countries may constantly angle to extract the most from each interaction, but they sacrifice trust, cooperation, and the predictability needed to tackle shared challenges. Indeed, Trump’s term saw strains in alliance networks and a U.S. retreat from multilateral leadership – a “fundamental shift” that favored “zero-sum…approaches over positive-sum strategies”, undermining America’s own global influence . Foreign policy experts have warned that a “transactional approach to foreign affairs will yield…instability” as actors compete for immediate gains instead of building stable spheres of influence .

While a transactional style can score quick victories or strike hard bargains, it often fails to address root problems. It treats symptoms (through deals or quid-pro-quos) rather than investing in solutions that require patience and cooperation. For example, international alliances and institutions, though sometimes frustratingly slow, exist to manage long-term issues collectively. Undermining them for short-term advantage can backfire. As one analysis notes, Trump’s abandonment of “collaborative efforts” and global commons leadership “threatens to undermine US global influence”, as other powers step into the void . Indeed, rivals like China have seized the opportunity to expand their influence when the U.S. turned inward. A more transactional world order might benefit the strongest players and corporations that can maneuver well, but it leaves smaller nations and the global commons worse off .

In sum, extreme short-term transactionalism is likely “a wrong way” to handle complex modern challenges. It may be a reaction to prior failures, but it risks trading one form of short-sightedness for another. The key question is: How should we address today’s grand issues – with transactional deal-making, or with longer-term vision and planning? To explore this, we can look at urgent global problems like climate change, migration, and technological disruption, and compare approaches.

Handling Climate Change: Transactional vs. Long-Term Strategies

Climate change is a textbook example of a crisis that punishes short-term thinking. Tackling it requires sustained long-range vision and global cooperation – essentially the opposite of a transactional, zero-sum approach. In recent years, we have seen a stark contrast between nations embracing long-term climate plans and those opting for short-term nationalism. Under President Trump, the U.S. pulled out of the Paris Agreement and prioritized domestic fossil fuel expansion, sending the message that “domestic energy dominance takes precedence over global climate cooperation” . This transactional stance treated climate commitments as a bad deal for the U.S. and relinquished leadership in global climate efforts. In contrast, other actors doubled down on forward-looking strategies. China, for instance, now treats climate action as an economic opportunity and part of its long-term development strategy . Beijing has set measurable targets for 2030 and 2035 (e.g. boosting renewables and cutting emissions) and integrated these into its five-year plans . The European Union, too, has a multi-decade vision (aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050) and enacts regulations and investments aligned with that goal.

The outcomes underscore the value of long-termism. China’s steady investment in solar, wind, and electric vehicles has made it a leader in clean tech manufacturing, demonstrating that “policy alignment, not slogans, drives progress” . The EU’s climate policies (like renewable energy targets and emissions trading) have helped bend its emissions curve downward over time. Meanwhile, the U.S.’s federal retreat under Trump left a leadership vacuum and uncertainty; even though states and businesses tried to fill the gap, crucial years were lost in the global effort . As a climate commentary bluntly put it, “Long-term, big-picture thinking is needed to make progress on climate change.” Short-term political expediency – for example, rolling back green policies to lower gas prices for immediate popularity – “holds back climate action”, because the benefits of climate measures are mostly long-term while costs are upfront.

Thus, on climate, a transactional mindset (treating it as just another deal or ignoring future harm for present gain) is clearly counterproductive. The better path is collaborative long-term planning – setting ambitious targets, investing in new technologies, and sticking to agreements so that all countries move forward together. Indeed, climate change has been called a “long-term national security issue” that demands planning beyond the next election . A purely bureaucratic approach can be slow, but a visionary plan (like the Paris Accord framework of progressively scaled-up pledges) provides direction and stability that piecemeal transactions cannot.

Handling Migration: Crisis Reactions vs. Long-Term Solutions

International migration is another multifaceted issue where short-term, transactional fixes often falter. During acute migrant crises – such as the surge of refugees to Europe in 2015-16 – governments tend to scramble with reactive measures. These can include emergency border closures, ad-hoc deals with transit countries, or stopgap humanitarian aid. For example, the EU’s 2016 deal with Turkey, wherein Turkey agreed to hold back refugees in exchange for EU funds, was a transactional arrangement born of immediate necessity. While it did sharply reduce inflows in the short term, it was criticized as Europe “shrugging off” its responsibilities by outsourcing the problem . Such measures may alleviate pressure temporarily but do not resolve the underlying drivers of migration or build enduring capacity to manage flows. As one study observed, the 2015 crisis forced European policymakers into “short-term decisions rather than long-term, durable solutions”, due to lack of preparedness .

In contrast, experts almost unanimously argue that migration challenges require a long-term, comprehensive vision. A policy analysis bluntly states: “Immigration is an irresolvable problem in the short term. Migration policies should follow a long-term vision,” addressing economic development, security, and social factors in origin and destination countries . This means investing in stability and opportunity in migrants’ home regions (to tackle root causes like conflict or lack of jobs), creating orderly legal migration pathways, and planning for integration of newcomers. It also requires international cooperation – no country can handle migration alone, and unilateral quick fixes (walls, pushbacks, or one-off deals) merely shift the burden. The UN Global Compact for Migration (2018) reflects this philosophy: it’s a non-binding agreement where 165 countries pledged to work together on safe, orderly migration, recognizing that only “joint co-responsibility” can address a global phenomenon .

The bureaucratic approach – slow negotiations on asylum reform, years-long integration programs – can be frustrating when crises erupt. But without a long-term framework, nations end up lurching from one emergency to the next. The 2015 EU refugee emergency showed that lack of planning and coordination made the crisis worse . By learning from that, Europe has tried to improve contingency plans, share responsibilities, and strengthen borders in a sustainable way . In sum, transactional measures (e.g. paying a neighbor to keep migrants away or using migration as a bargaining chip) might offer temporary relief but no lasting solution. A forward-looking, values-based strategy – albeit slower – addresses the issue at its source and over the long haul, which is ultimately more effective and humane.

Navigating Technological Evolution: Planning vs. Adaptability

Technology is evolving at breakneck speed, transforming economies and societies. Here, the point that “the tech world is certainly not a carefully planned environment” is very salient. Many of the greatest tech innovations of our time – the internet, smartphones, social media, artificial intelligence – emerged from dynamic, decentralized processes: startup culture, academic research, even military R&D projects. Governments often struggle to anticipate or controlthese developments with rigid plans. By the time a traditional public-sector plan is executed, the tech landscape may have shifted radically. As an observer quipped, “a parliament takes two years to pass [a policy]; in that time, the entire technological landscape shifts.” This highlights the mismatch between slow bureaucratic processes and the “volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity” of the digital age .

Does this mean a transactional, hands-off approach is better for technology? Not quite. Simply leaving tech to the short-term whims of the market can lead to chaos or societal harms (consider unregulated social media contributing to disinformation, or AI algorithms deployed without oversight). What it does mean is that governance of technology should be flexible and adaptive rather than centrally micromanaged. In practice, this could involve setting broad long-term goals (e.g. investing in science education, funding fundamental research, crafting ethical frameworks for AI) while remaining agile in implementation. For instance, the U.S. government historically funded long-range technological research (through agencies like DARPA) that paid off over decades – but it did so by empowering innovators rather than dictating every step. DARPA program managers are given missions and budgets, not step-by-step plans, allowing them to fund breakthrough ideas quickly – an approach credited with birthing the Internet and GPS . This blend of vision with agility shows how public policy can foster tech evolution without rigid central planning.

Different geopolitical players illustrate varying approaches to tech. China famously uses five-year plans and state directives to steer technological development – for example, its “Made in China 2025” plan to dominate high-tech industries, or its national AI strategy aiming for global leadership by 2030. This top-down planning, backed by massive investments, has driven rapid progress in areas like 5G, renewable energy tech, and AI. However, even China’s planners face the unpredictability of innovation – hence they often adjust policies on the fly and encourage local experiments. The United States, by contrast, leans on free-market innovation: its tech giants (Google, Apple, Facebook, etc.) arose in a relatively laissez-faire system. This produced astounding innovation and wealth, but also unforeseen societal challenges (privacy issues, monopoly power, job disruption) that the government is now scrambling to address retroactively. Europe takes yet another path: it generally doesn’t house as many Big Tech innovators, but it focuses on regulating technology’s impact (e.g. GDPR for data privacy, proposed AI Act for algorithmic accountability) – essentially trying to plan the rules of the game to protect societal values in the long run. Each model has merits and downsides: too much planning can stifle entrepreneurship, yet too little can let short-term profit chase cause long-term damage.

The key may lie in adaptive governance – having a strategic vision for harnessing technology for public good, but iterating and adjusting as technologies develop. In other words, public servants should indeed “develop a vision for the future” in areas like digital infrastructure, AI ethics, and workforce reskilling. But that vision must be coupled with nimble, transaction-speed responses when new tech disruptions arrive. The tech world’s unpredictability teaches governments to plan for the capacity to adapt, not a fixed end-state . As one governance expert suggests, instead of rigidly asking “What will the future hold and how do we plan for it?”, policymakers should ask “What capabilities enable us to handle whatever happens?” . This mindset transcends the false choice between transactional improvisation and static long-term plans, aiming for a middle ground of long-term direction with short-term adaptability.

Diverging Approaches: US, EU, and China in Context

It’s illuminating to compare how the United States, Europe, and China balance transactional vs. planned strategies on these big issues.

United States: Traditionally, U.S. leadership after WWII combined values-based long-term strategy (building alliances, institutions, and a stable world order) with economic dynamism. In recent years, however, U.S. politics became more polarized and short-term oriented, culminating in Trump’s openly transactional doctrine. The Trump era’s “deeply pragmatic, perhaps short-sighted” America First stance saw the U.S. withdraw from global commitments (climate accords, trade agreements) and renegotiate deals for immediate gain. This represented a break from the past – a shift from enlightened long-term self-interest to narrow short-term interest . The result was mixed: some deals (e.g. revised NAFTA, now USMCA) brought marginally better terms, but the U.S.’s reputation as a reliable partner was damaged. Under President Biden, the U.S. tried to swing back toward a more traditional approach – rejoining the Paris Agreement, investing in climate via a 10-year plan (the Inflation Reduction Act’s climate provisions), and repairing alliances. Still, the U.S. remains somewhat caught between its innovative, agile private sector and a governance system prone to gridlock. Major strategic undertakings (like consistent climate policy or immigration reform) often fall victim to election reversals and partisan fights, reflecting the challenge of long-term planning in a volatile democracy.

European Union: The EU is often seen as the epitome of the bureaucratic, long-term planning mindset. Brussels issues decade-long strategies (e.g. Europe 2030 agenda, Green Deal), and member states negotiate policies through careful, consensus-driven processes. On issues like climate and migration, the EU tends to emphasize multilateral cooperation and sustained frameworks – for example, binding renewable energy targets, or the Dublin Regulation for asylum responsibility (however flawed it may be). This approach yields visionary commitments (like carbon-neutral Europe by mid-century) but also slow adaptation. When a crisis hits (the Eurozone debt crisis, the refugee influx, or the COVID-19 pandemic), the EU often scrambles and only later overhauls its systems. Indeed, critics say the EU was ill-prepared and slow in 2015, leading to transactional stopgaps like the Turkey deal . However, the EU learns and tends to build new long-term mechanisms afterward (e.g. a permanent Border and Coast Guard, pandemic recovery funds). Culturally, European publics expect government to plan for social welfare and regulation more than in the U.S., and there is less tolerance for overt transactionalism that violates values (such as sacrificing human rights for quick deals). Going forward, Europe is trying to stay true to its values-based long game while also becoming more geopolitically “realistic” in a competitive world – a balance that involves being principled but not naïve or static .

China: China operates on a fundamentally different political model that enables long-term planning. The Communist Party sets strategic goals looking decades ahead – for instance, the goal to become a “fully developed, rich, and powerful” nation by 2049 (the PRC’s centenary), or peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060. Five-Year Plans break these visions into phased programs. This long-horizon, centralized planning has yielded impressive results in infrastructure, industrial growth, and poverty reduction. China can mobilize resources and stay the course more easily without frequent leadership changes or public dissent. For example, in climate policy, China’s recent 2035 roadmap and its integration of climate action into economic planning stand out as a model of consistent ambition . It has treated renewable energy and electric vehicles not as burdens, but as industries to dominate for future prosperity . Likewise, in technology, China invests heavily in domestic innovation and has a strategy to reduce reliance on foreign tech (e.g. developing its own semiconductor supply chain), reflecting long-term strategic thinking. However, China’s approach is not without short-term pragmatism. It can be highly transactional in diplomacy – for instance, leveraging trade or investment for political concessions from smaller countries, or its Belt and Road Initiative deals that swap infrastructure loans for influence. And despite its climate plans, China still builds coal plants to ensure near-term energy security, illustrating a practical (some might say short-sighted) trade-off. The advantage China has is an ability to combine long-term vision with quick policy shifts when needed, unencumbered by electoral politics. The downside is that without democratic checks, long-term plans can have destructive side effects (e.g. environmental harm, overcapacity) before they’re corrected.

In summary, the U.S., EU, and China each mix transactional and strategic elements differently. The U.S. has agility and innovation but sometimes at the cost of consistency; the EU has vision and principle but often moves slowly; China has strategic clarity and capacity but may over-centralize decisions. These differences suggest that no single approach is perfect – and that perhaps the ideal lies in synthesizing the strengths of each.

Toward a Balanced Approach for Complex Issues

So, what is the “best way” to handle the great issues of our time? The analysis above suggests that neither pure transactionalism nor old-school bureaucratic planning alone is sufficient. Grand challenges like climate change, migration, and technological revolution are unprecedented in scale and complexity. They demand both foresight and flexibility. Here are some key principles for a better approach:

Long-Term Vision and Values: We absolutely need plans and goals looking 10, 20, 50 years ahead. Whether it’s halting global warming, managing demographic shifts, or adjusting to AI-driven economies, a long view is critical. Governments should restore practices of strategic foresight – for example, scenario planning, expert advisory councils, and investing in future generations. As one Canadian policy expert urged, “It is time to take a longer view” , rather than governing day-to-day by opinion polls or tweets. Clear long-term targets (net-zero emissions, sustainable development goals, etc.) provide direction and can mobilize public and private effort over time.

Short-Term Action and Adaptability: A long vision must be paired with agile execution. The world is too unpredictable for rigid blueprints. Governments should build adaptive capacity – the ability to respond to crises or technological disruptions in real time, without derailing the long-term agenda. This might involve setting up rapid-response units, using “agile” project methods in public administration, and empowering local authorities or agencies to experiment and share best practices. In essence, bureaucracy must become leaner and more responsive, focusing on outcomes over process. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, those who adapted quickly (like Estonia shifting to e-services in days ) fared better than those stuck in months of committee meetings. Being transactional in the implementation phase – i.e. making pragmatic deals and quick fixes when necessary – can complement a strategic vision, as long as those transactions serve the larger goal and are course-corrected as needed.

Global Cooperation with Reciprocity: Issues like climate and migration cross borders; no country can solve them alone. A cooperative, multilateral approach is generally superior for such collective-action problems. That said, cooperation need not mean naive trust – it can be enforced with reciprocal, “transactional” elements to ensure everyone pulls their weight. For example, the Paris Climate Agreement has each country set pledges and periodically up the ante, which combines long-term cooperation with a mechanism of accountability (each nation expects others to also increase efforts – a kind of iterative transaction). Similarly, migration compacts can involve mutual commitments: development aid in exchange for better border management, or resettlement slots in exchange for processing asylum claims – but all under an overarching framework that recognizes shared responsibility rather than one-off bargains. The key is to avoid beggar-thy-neighbor moves and instead structure deals that advance collective interests as well as national interests (what diplomats call “enlightened self-interest”).

Engaging Public and Private Stakeholders: The complexity of technological and societal change means governments can’t plan or execute alone. Businesses, cities, civil society, and scientists all have roles. A modern approach leverages these networks. For instance, tech governance works best when regulators collaborate with industry and researchers to understand emerging trends (as seen in some “regulatory sandbox” approaches that let companies and regulators learn together ). On climate, sub-national actors (states, provinces, corporations) often innovate faster than national governments; harnessing that can reconcile short-term innovation with long-term policy. Public servants should act as conveners and enablers of these efforts, not just top-down planners. This reduces the risk of government plans being blindsided by real-world developments, because the planning process itself becomes more dynamic and informed.

In essence, the path forward lies in melding the foresight of the planner with the agility of the dealmaker. We need the bureaucrat’s long memory and institutional knowledge to sketch the future, and the entrepreneur’s quick reflexes to seize or mitigate immediate events. Geopolitics should not be a mere series of transactions with no vision, but nor can it cling to a grand vision oblivious to on-the-ground realities.

Conclusion

The evolution from traditional short-term politics to an even more transactional geopolitics in recent years has been a double-edged sword. It arose from valid frustrations – the feeling that lofty long-term talk wasn’t delivering – but it risks overshooting, replacing inadequate foresight with outright myopia. Trump’s transactional turn exemplified how foreign policy geared only to immediate advantage can undermine the very global stability and alliances that, in the long run, also serve national interest . On the other hand, the answer is not to return to complacent planning that cannot adjust to a fast-changing world. The stark truth is that issues like climate change, migration, and technological upheaval demand both commitment to the future and agility in the present.

When asked whether a “transactional” or “bureaucratic planned” approach is better, the reality is: we need the best of both, and the excesses of neither. Long-term challenges can only be met with long-term thinking – there is no transactional shortcut to stopping global warming or managing global migration flows . Yet, implementing those long-term solutions in a chaotic world requires pragmatic deal-making, iterative adjustments, and sometimes bold, immediate moves. The technological revolution, especially, has taught us that top-down control is often futile; adaptability and innovation are paramount.

In the final analysis, geopolitics should be neither blindly transactional nor blindly bureaucratic. Instead, it should be strategic – which implies having a vision of the desired future, and cleverly orchestrating both short-term and long-term actions to get there. A strategic actor knows when to compromise for an interim gain and when to invest patiently for a bigger payoff later. For the EU, US, China and others, the challenge is to escape the trap of short-termism without becoming inflexible. The world will benefit if leaders can transcend the simplistic yes/no of “transactional vs planning” and move toward a nuanced statecraft that is principled, far-sighted, and yet responsive. In a time of rapid change, that blend is our best hope to handle the defining issues of our era.

Sources:

Foreign Policy – “Trump Is Ushering In a More Transactional World”

Other News – “Europe at the Crossroads: Navigating a New Cold War in a Transactional World”

Medium (The New Climate) – “Why Short-Term Thinking Is Holding Back Climate Action”

School of Public Policy – “Political short-termism… It is time to take a longer view.”

PMC Journal – “Long-Lasting Solutions to the Problem of Migration in Europe”

FPIF – “How China Is Turning Climate Action into Economic Strategy”